Clinical Question

Among patients with early septic shock, does a personalized hemodynamic resuscitation protocol targeting capillary refill time improve outcomes compared to usual care?

TL;DR

A personalized resuscitation protocol targeting capillary refill time reduced the duration of organ support in septic shock patients. The intervention group received less fluid, more targeted vasopressor adjustments, and selective inotrope use-resulting in faster recovery without changing mortality. This represents a shift from one-size-fits-all sepsis bundles toward bedside phenotyping.

The Deets

The optimal resuscitation strategy for septic shock remains one of intensive care's most contentious questions. Recent trials comparing liberal versus restrictive fluids and high versus low MAP targets have failed to move the needle on mortality. The problem might be that we've been asking the wrong question. Instead of debating whether all patients need more or less of something, maybe we should be asking which patients need what.

ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 tested a personalized approach. The trial enrolled 1,467 patients across 86 ICUs in 19 countries, randomizing them within 4 hours of meeting septic shock criteria. Patients had already received a median of 1,500 mL of fluids and were on norepinephrine at a median dose of 0.22 μg/kg/min-this was early shock, but not that early.

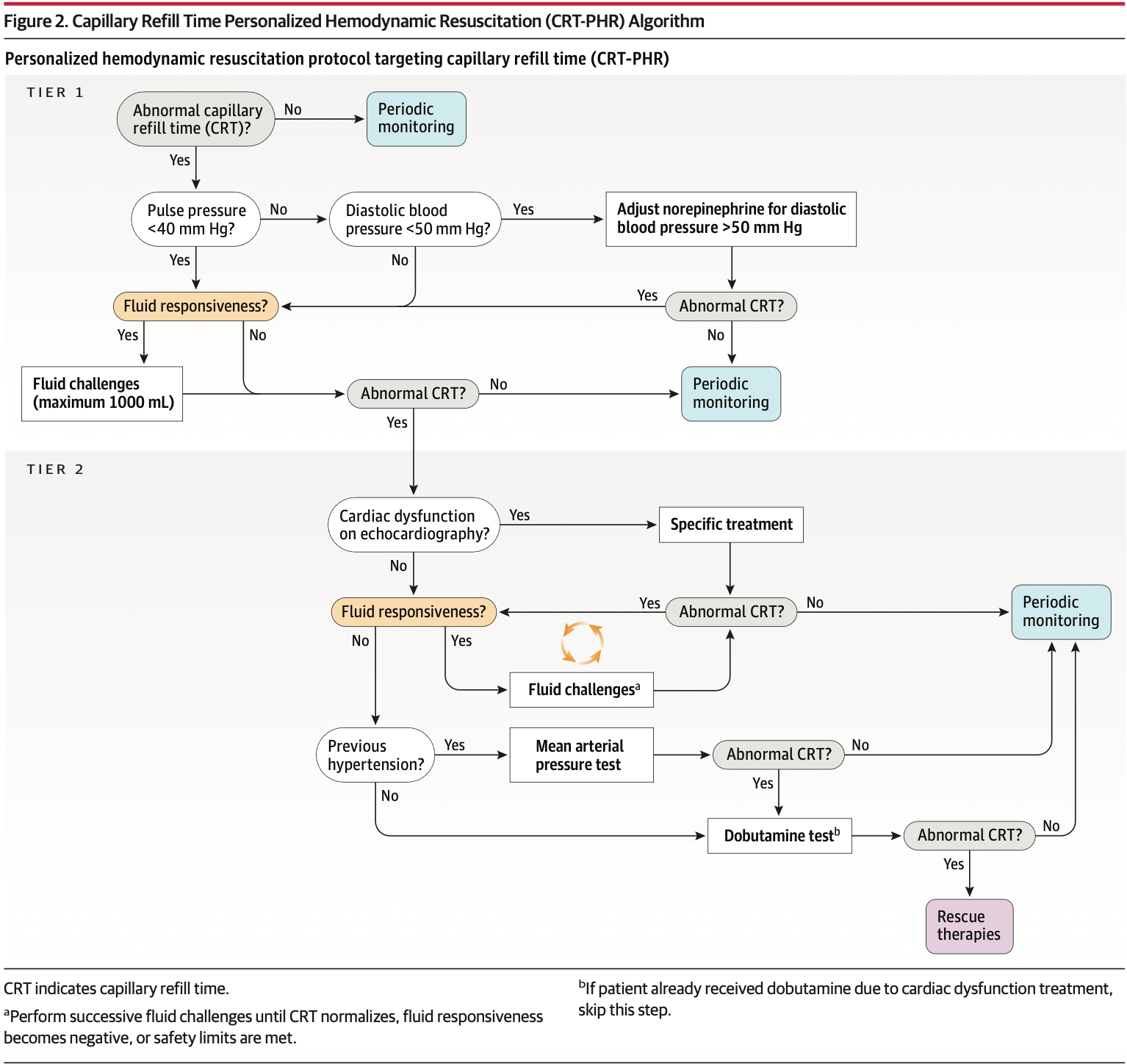

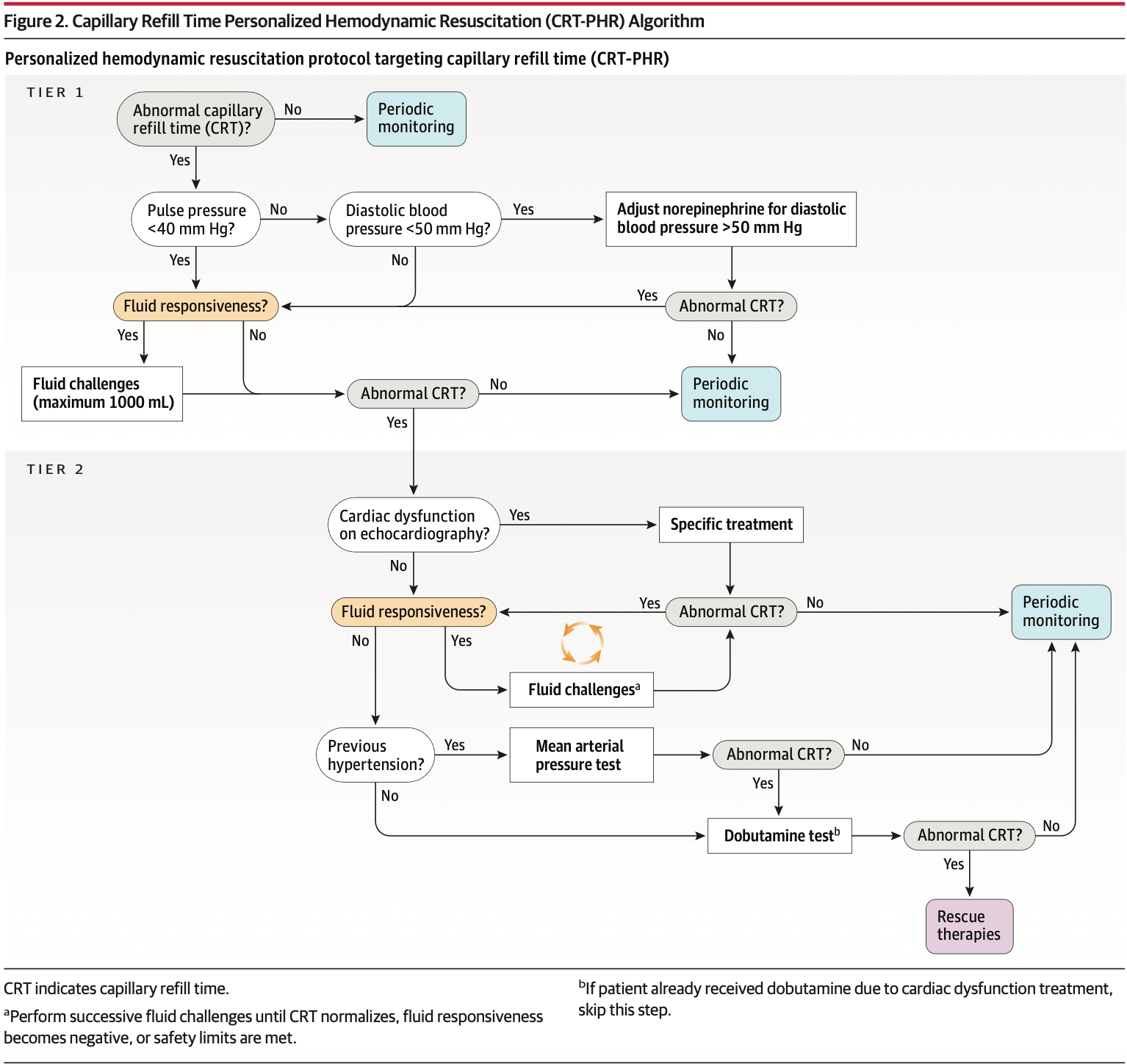

The intervention was a 6-hour protocol targeting capillary refill time normalization (≤3 seconds). The protocol used sequential assessments: pulse pressure to identify low stroke volume states, diastolic blood pressure to detect severe vasoplegia, fluid responsiveness testing before every fluid bolus, and bedside echo to identify cardiac dysfunction. Based on these assessments, patients received tailored fluids, vasopressors, or inotropes.

Here's what makes this interesting: 36% of patients in the intervention group started with normal capillary refill time and received no additional interventions. They were left alone. Another 65% of patients who needed intervention normalized their capillary refill time with simple tier 1 maneuvers-fluid boluses for those with low pulse pressure who were fluid responsive, or vasopressor adjustments for those with low diastolic pressure. Only 35% needed the more complex tier 2 interventions involving echocardiography and hemodynamic testing.

The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 Investigators for the ANDROMEDA Research Network, Spanish Society of Anesthesiology, Reanimation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR), and Latin American Intensive Care Network (LIVEN). Personalized Hemodynamic Resuscitation Targeting Capillary Refill Time in Early Septic Shock: The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025;334(22):1988–1999. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.20402

At 6 hours, the groups looked different. The intervention group received less fluid (595 mL vs 847 mL), had lower central venous pressures (9.1 vs 9.8 mm Hg), received more dobutamine (12.3% vs 5.3%), and had more patients with normalized capillary refill time (85.9% vs 61.7%). Lactate levels were slightly lower (3.2 vs 3.5 mmol/L), but the difference was modest.

The primary outcome was a hierarchical composite assessed at 28 days: mortality first, then duration of vital support (vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, or kidney replacement therapy), then hospital length of stay. Using a win ratio analysis, the intervention group had a win ratio of 1.16 (95% CI 1.02-1.33, P=0.04).

Breaking that down: 28-day mortality was identical at 27% in both groups. Hospital length of stay didn't differ meaningfully (15.3 vs 16.2 days). The difference came from duration of vital support-median 3.0 days in the intervention group versus 4.0 days in usual care. Patients in the personalized resuscitation group got off vasopressors, ventilators, and dialysis faster.

The trial enrolled a sick population. Nearly half were on mechanical ventilation at baseline, one in five was receiving a second vasopressor, and median APACHE II scores were 18-19. This wasn't mild shock.

Protocol adherence was high-only 6% of patients had protocol violations. The intervention was feasible across diverse settings, from high-income ICUs with advanced monitoring to resource-limited units relying on basic assessments. The fact that most patients responded to simple tier 1 interventions suggests the protocol is scalable.

Design

Multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial

N=1,467

Personalized hemodynamic resuscitation targeting capillary refill time (n=720)

Usual care (n=747)

Follow-up: 28 days (with 90-day mortality data collected)

86 ICUs across 19 countries in the Americas, Europe, and Asia

Population

Inclusion Criteria

Adults ≥18 years old

Within first 4 hours of septic shock onset, defined as:

Suspected or confirmed infection

Serum lactate ≥2.0 mmol/L

Receiving norepinephrine to maintain MAP ≥65 mm Hg after ≥1000 mL IV fluid

Exclusion Criteria

More than 4 hours after septic shock criteria met

Anticipated surgery or dialysis in next 6 hours

Life expectancy <90 days due to disease progression

Refractory shock (assessed by treating clinician)

Do-not-resuscitate status

Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis

Severe ARDS at randomization

Active bleeding

Pregnancy

Capillary refill time could not be accurately assessed

Baseline Characteristics

From the intervention group

Demographics: Median age 66 years (IQR 52-74), 42% female, median weight 70 kg

Severity: APACHE II 19 (IQR 14-24), SOFA 8 (IQR 7-11)

Comorbidities: Chronic hypertension 23%, diabetes 24%, chronic pulmonary disease 12%

Infection source: Abdominal 49%, respiratory 18%, urinary 21%

Organ support at baseline: Invasive mechanical ventilation 47%, vasopressin 24%, median norepinephrine dose 0.23 μg/kg/min

Perfusion markers: Capillary refill time >3 seconds in 58%, median lactate 3.7 mmol/L, median capillary refill time 4.0 seconds

Interventions and Controls

Randomly assigned to a group:

Personalized hemodynamic resuscitation (CRT-PHR) - 6-hour protocol with hourly capillary refill time assessments, targeting normalization (≤3 seconds). Protocol implemented in 2 tiers:

The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 Investigators for the ANDROMEDA Research Network, Spanish Society of Anesthesiology, Reanimation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR), and Latin American Intensive Care Network (LIVEN). Personalized Hemodynamic Resuscitation Targeting Capillary Refill Time in Early Septic Shock: The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025;334(22):1988–1999. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.20402

Tier 1: Pulse pressure assessment. If <40 mm Hg → fluid responsiveness testing → 500 mL fluid bolus if responsive (up to 1000 mL). If pulse pressure ≥40 mm Hg but diastolic pressure <50 mm Hg → titrate norepinephrine to achieve diastolic pressure ≥50 mm Hg

Tier 2 (if capillary refill time still abnormal): Basic echocardiography to assess ventricular function → treat cardiac dysfunction if present → reassess fluid responsiveness → additional fluid boluses if responsive → if chronic hypertensive, trial of higher MAP (80-85 mm Hg) for 1 hour → if still abnormal, dobutamine 5 μg/kg/min for 1 hour

Patients with normal capillary refill time at baseline received no additional interventions unless capillary refill time became abnormal during hourly reassessments

Administered by trained medical operators dedicated to protocol execution

Usual care - Treatment according to local protocols and international guidelines. Fluid responsiveness assessment and echocardiography allowed but not mandated. Capillary refill time measured only at baseline and 6 hours. Care delivered by attending intensivists

Outcomes

Comparisons are personalized resuscitation vs. usual care.

Primary Outcome

Hierarchical composite of mortality, duration of vital support, and length of hospital stay at 28 days

What's a Win Ratio + Hierarchical composite? The win ratio compares every patient in one group to every patient in the other by ranking outcomes hierarchically (death first, then duration of organ support, then hospital length of stay). A win ratio of 1.16 means the intervention group "won" 16% more pairwise comparisons than it lost—capturing benefits beyond mortality that traditional analyses would miss.

Win ratio: 1.16 (95% CI 1.02-1.33, P=0.04)

Wins in intervention group: 131,131 (48.9%)

Wins in usual care group: 112,787 (42.1%)

Ties: 24,151 (9.0%)

Component breakdown:

Individual wins for death: 19.1% vs 17.8%

Individual wins for duration of vital support: 26.4% vs 21.1%

Individual wins for length of hospital stay: 3.4% vs 3.2%

Secondary Outcomes

Outcome | Personalized Resuscitation | Usual Care |

|---|---|---|

28-day mortality | 26.5% | 26.6% |

Vital support-free days within 28 days, median | 23.0 days (IQR 0-25) | 22.0 days (IQR 0-25) |

Length of hospital stay, median | 13.0 days (IQR 8-25) | 15.0 days (IQR 8-28) |

Duration of vital support, median | 3.0 days | 4.0 days |

Vital support-free days: Mean 16.5 days (SD 11.3) in intervention group vs 15.4 days (SD 11.4) in usual care (proportional odds ratio 1.28, 95% CI 1.06-1.54)

Subgroup Analysis

No significant treatment effect modification was observed across any prespecified subgroups:

Age

Sex

Baseline APACHE II score

Baseline capillary refill time (normal vs abnormal)

Geographic region

Infection source

Adverse Events

Event | Personalized Resuscitation | Usual Care |

|---|---|---|

Protocol deviations | 111 patients (15%) | N/A |

Protocol violations | 44 patients (6%) | N/A |

Suspected serious adverse reactions | Similar between groups | Similar between groups |

Note: DAP augmentation, MAP tests, and dobutamine tests were not conducted in some patients due to preemptive safety considerations (6, 13, and 19 patients respectively). One dobutamine test was stopped due to hypotension, which reversed after discontinuation.

Criticisms

Open-label design with a subjective component to cessation of organ support. Clinicians knowing treatment allocation may have influenced decisions about when to stop vasopressors or extubate, potentially biasing the primary outcome.

The intervention wasn't just the protocol-it was the protocol plus dedicated trained personnel at the bedside for 6 hours. We can't separate the effect of protocolized care from the effect of additional bedside assessment and resources.

Modest separation between groups. The difference in fluid administration (250 mL) and vasopressor use (3 percentage points) was smaller than in other trials that showed no benefit. This raises questions about whether the protocol itself drove outcomes or whether it was simply optimization of basic fluid stewardship.

Protocol complexity limits understanding of which components mattered. Was the benefit from withholding fluids in patients with normal capillary refill time? From better fluid responsiveness assessment? From diastolic pressure augmentation? From selective inotrope use? The bundle approach prevents us from knowing.

Some protocol elements lack strong evidence. Titrating vasopressors to achieve diastolic pressure ≥50 mm Hg and the MAP test to 80-85 mm Hg in hypertensive patients are physiologically plausible but haven't been validated in isolation.

Capillary refill time assessment has known limitations: interobserver variability, influence of ambient temperature, skin pigmentation effects, and peripheral vascular disease. The trial standardized measurement technique but real-world reliability outside research settings is uncertain.

The hierarchical composite outcome, while statistically valid, makes clinical interpretation challenging. A win ratio of 1.16 doesn't translate easily to bedside decision-making the way an absolute mortality reduction would.

No assessment of time from ICU admission to protocol initiation. This matters because early resuscitation timing is critical, and delays could have attenuated treatment effects.

Limited assessment of downstream consequences. Did faster liberation from organ support lead to better functional outcomes? More ICU readmissions? The trial didn't capture quality of life, functional status, or post-ICU syndrome.

Dashevsky's Dissection

For patients: This trial suggests that personalized resuscitation can get you off life support faster without increasing your risk of dying. That matters-not just for getting out of the ICU sooner, but because every extra day on a ventilator or vasopressors increases the risk of complications. The approach is cautious where it should be (withholding fluids in patients who don't need them) and aggressive where it counts (targeted interventions for those who do).

For pulmonary and critical care physicians: ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 is telling us that the future of sepsis resuscitation isn't about universal fluid targets or MAP goals. It's about phenotyping patients at the bedside and matching interventions to physiology. Capillary refill time is a surprisingly useful tool for this. It's quick, it's free, and it correlates with microcirculatory function in a way that lactate and central venous pressure don't.

The protocol's structure is actually its strength. Most patients got better with basic tier 1 interventions-fluid if they needed it, vasopressors if their diastolic pressure was low. Only a third needed the complex stuff. That tells me we're probably overdoing it with routine echocardiography and advanced monitoring in patients who just need thoughtful clinical assessment.

But here's the implementation challenge: this protocol required dedicated trained personnel at the bedside for 6 hours. That's not happening in most ICUs. We're understaffed, overtasked, and managing multiple crashing patients simultaneously. The median time on protocol was 6 hours, but the median duration of benefit extended well beyond that-suggesting that early optimization matters most. The question is whether we can integrate these principles into routine care without needing a research coordinator at every bedside.

The other question is whether capillary refill time is really the magic marker here, or whether it's just a proxy for "stop and reassess." The trial withheld fluids in 36% of patients who had normal capillary refill time at baseline. That's huge. How many times have we given fluids to septic shock patients simply because their lactate was 3.5 mmol/L, even though their perfusion looked fine? This protocol forced clinicians to justify every fluid bolus with a physiologic rationale. Maybe that's the real lesson.

For the health system: This is where things get interesting. The intervention didn't reduce mortality, but it reduced the duration of organ support by a median of 1 day. In a resource-constrained system, that could translate to better ICU throughput, lower costs, and more capacity for other critically ill patients. But those benefits only materialize if we can actually implement the protocol without adding personnel costs that offset the savings.

The trial was conducted in 86 ICUs across 19 countries, including resource-limited settings. The fact that it worked in diverse environments suggests scalability, but we need pragmatic implementation studies to figure out how to make this work in real-world workflows.

The broader point is this: we've spent two decades arguing about whether septic shock patients need more fluids or less, higher MAPs or lower, lactate targets or central venous oxygen saturation. ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 suggests we've been having the wrong debate. The right question isn't what to do-it's who needs what. Personalized resuscitation based on bedside phenotyping is feasible, and it works. Now we need to figure out how to make it routine.

The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 Investigators for the ANDROMEDA Research Network, Spanish Society of Anesthesiology, Reanimation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR), and Latin American Intensive Care Network (LIVEN). Personalized Hemodynamic Resuscitation Targeting Capillary Refill Time in Early Septic Shock: The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025;334(22):1988–1999. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.20402