Clinical Question

Among critically ill adults receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, does early use of an automated closed-loop ventilation system increase ventilator-free days at day 28 compared with protocolized conventional ventilation?

TL;DR

Automated closed-loop ventilation using INTELLiVENT-ASV didn't increase ventilator-free days at day 28 compared to protocolized conventional ventilation in a broad ICU population. Both groups had a median of about 16 days free from the ventilator. The automated system improved ventilation quality metrics and reduced episodes of severe hypoxemia and hypercapnia, but this didn't translate into meaningful clinical benefits when conventional ventilation was already highly protocolized.

The Deets

Closed-loop ventilation systems promise to solve one of critical care's most labor-intensive challenges: continuously optimizing ventilator settings in response to a patient's changing condition. INTELLiVENT adaptive support ventilation (ASV) is among the most sophisticated systems, using breath-by-breath analysis to automatically adjust tidal volume, respiratory rate, FiO₂, and PEEP based on real-time patient physiology.

The ACTiVE trial enrolled 1,201 critically ill adults across 7 ICUs in the Netherlands and Switzerland. Patients were randomized within 1 hour of intubation to either automated closed-loop ventilation or protocolized conventional ventilation. This is one of the largest randomized trials ever conducted on mechanical ventilation in the ICU.

The trial population was heterogeneous. Only one-third were intubated for respiratory failure. About 25% were intubated for neurological dysfunction, 25% following cardiac arrest, and the remainder for postoperative ventilation or airway protection. This matters because many of these patients-particularly those with neurological impairment or post-cardiac arrest-often require ventilation primarily for depressed consciousness rather than respiratory failure. They're typically weaned to minimal settings quickly but remain intubated for days waiting for mental status to improve.

Both groups received highly protocolized care. This wasn't closed-loop ventilation versus "usual care"-it was closed-loop versus expert-driven conventional ventilation. The conventional group had standardized lung-protective settings, daily sedation interruptions, and-critically-readiness for weaning assessed three times daily. That frequency of weaning assessment exceeds standard practice in most ICUs and likely represents near-optimal conventional ventilation.

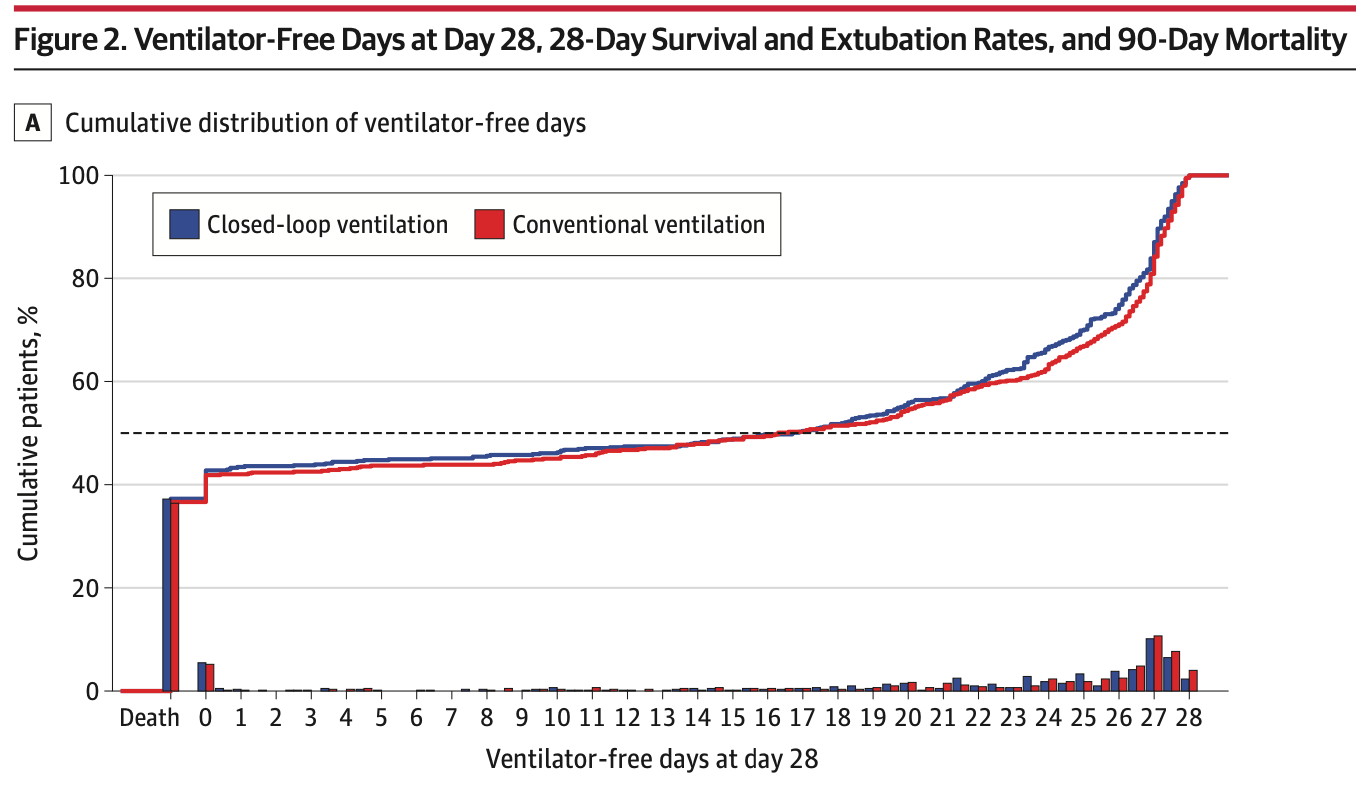

The primary outcome was ventilator-free days at day 28. The result: median 16.7 days in the closed-loop group versus 16.3 days in conventional ventilation (odds ratio 0.91, 95% CI 0.77-1.06, P=0.23). No difference.

Secondary outcomes were mostly neutral. Twenty-eight-day mortality was identical at 27% in both groups. Duration of ventilation among survivors didn't differ significantly (3.3 vs 2.6 days, P=0.05). ICU and hospital mortality, length of stay, and rates of ventilator-associated complications were all similar.

Where closed-loop ventilation did show a difference was in ventilation quality. In a subset of 152 patients with granular breath-by-breath data available, the closed-loop group spent 48% of time in optimal ventilation zones versus 37% in conventional ventilation. They spent less time in critical zones (12% vs 36%). Severe hypoxemia (PaO₂ <55 mm Hg) occurred in 16% of the closed-loop group versus 21% of controls. Severe hypercapnia (PaCO₂ >55 mm Hg with pH <7.35) occurred in 20% versus 24%. Fewer patients in the closed-loop group required rescue therapies, primarily prone positioning (9% vs 14%), though this didn't reach statistical significance after multiplicity adjustment.

The closed-loop system was used consistently once initiated-patients spent a median 96% of ventilation time under the correct strategy. Among the subset of patients where protocol-specific settings were tracked, the ARDS, chronic hypercapnia, and brain injury presets were used in only 3%, 2%, and 11% of patients respectively-consistent with the low burden of these specific conditions in the trial.

So what happened? Why didn't physiologic improvements translate into clinical benefits?

First, about 60% of patients either died early (20%) or were successfully extubated within 3 days (40%). This is much higher than typical respiratory failure cohorts. There may not have been enough exposure to the intervention for cumulative benefits to accrue. The advantages of automated adaptation presumably increase with longer ventilation duration, when more opportunities exist for optimization.

Second, the control group received exceptional care. Screening for weaning readiness three times daily is resource-intensive and uncommon in practice. The conventional ventilation here likely represents a ceiling of what expert-driven care can achieve, making it difficult for automation to demonstrate superiority.

Third, the patient population may have diluted treatment effects. Patients ventilated for neurological impairment or following cardiac arrest often don't need complex ventilator management-they need minimal settings and time for their brain to recover. Closed-loop ventilation has limited value when the barrier to extubation isn't respiratory physiology but mental status.

Design

International, multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial

N=1,201

Automated closed-loop ventilation using INTELLiVENT-ASV (n=602)

Protocolized conventional ventilation (n=599)

Follow-up: 90 days

7 ICUs in the Netherlands and Switzerland

Population

Inclusion Criteria

Adults ≥18 years old

Less than 1 hour elapsed since initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU

Expected to require invasive mechanical ventilation for ≥24 hours

Exclusion Criteria

Age <18 years

Unavailability of ventilator equipped with closed-loop system

Pregnancy

Invasive ventilation >1 hour in ICU or >6 hours before ICU admission

Participation in another interventional trial

Recent pneumonectomy or lobectomy

BMI >40

Premorbid restrictive lung disease

ECMO

Unreliable pulse oximetry

Neuromuscular disorders expected to prolong ventilation

Previous randomization

Inability to obtain informed consent

Baseline Characteristics

From the closed-loop group

Demographics: Median age 63 years (IQR 51-73), 36% female, median BMI 26

Severity: SAPS II 54 (IQR 41-64), SOFA score 8 (IQR 6-11)

Type of admission: Medical 86%, emergency surgery 13%, planned surgery 2%

Reason for intubation: Respiratory failure 30%, cardiac arrest 28%, neurological 26%, postoperative 9%, airway protection 5%

Time from ventilation start to randomization: Median 0.6 hours (IQR 0.3-1.0)

Baseline ventilation: Tidal volume 6.6 mL/kg PBW (IQR 5.8-7.4), PEEP 7.7 cm H₂O (IQR 5.0-9.9), FiO₂ 0.60 (IQR 0.50-0.90)

Gas exchange: P/F ratio 190 mm Hg (IQR 106-307), PaCO₂ 44 mm Hg (IQR 38-52), pH 7.28 (IQR 7.19-7.36)

Sepsis: 15%

Hypoxemic respiratory failure (P/F <200): 15%

Interventions and Controls

Randomly assigned to a group:

Automated closed-loop ventilation: INTELLiVENT-ASV initiated within 1 hour of randomization. The system uses the Otis equation and Mead formula to determine optimal tidal volume and respiratory rate that minimizes work of breathing and mechanical power based on predicted body weight and end-tidal CO₂ targets. FiO₂ and PEEP continuously adjusted according to SpO₂ targets. Optional presets available for ARDS, chronic hypercapnia, or brain injury (predefined target adjustments, not different proprietary algorithms). QuickWean function recommended for automated weaning. Target zones for SpO₂ and end-tidal CO₂ automatically adjusted and could be fine-tuned by clinicians. Patients spent median 96% of ventilation time under correct strategy.

Protocolized conventional ventilation: Volume-controlled, pressure-controlled, or pressure support ventilation. Any other automated or closed-loop system prohibited (including NAVA, SmartCare/PS, proportional assist ventilation). Lung-protective ventilation mandated: low tidal volumes, plateau pressure limitation, adequate PEEP and oxygenation targets. Analgosedation preferred over hypnosedation. Daily sedation interruptions actively encouraged.

Weaning protocols (standardized in both groups):

Readiness for weaning assessed at least 3 times daily in both groups

Closed-loop group: Transitions from controlled to assisted ventilation and weaning fully automated. Automated or conventional SBTs used.

Conventional group: Patients assessed 3 times daily for transition to pressure support. Weaning guided by gradual protocolized reductions. Conventional SBTs used.

Extubation criteria (identical): Awake and cooperative, hemodynamically stable without high-dose vasopressors, P/F >150 on FiO₂ ≤0.40, temperature 36-38°C, strong cough, respiratory rate <35/min

Tracheostomy generally avoided within 10 days unless prolonged ventilation, impaired consciousness, ICU-acquired weakness, or extubation failure occurred

Outcomes

Comparisons are closed-loop vs. conventional ventilation.

Primary Outcome

Ventilator-free days at day 28

Median: 16.7 days (IQR 0.0-26.1) vs. 16.3 days (IQR 0.0-26.5)

Odds ratio: 0.91 (95% CI 0.77-1.06, P=0.23)

Sinnige JS, Buiteman-Kruizinga LA, Horn J, et al. Effect of Automated Closed-Loop Ventilation vs Protocolized Conventional Ventilation on Ventilator-Free Days in Critically Ill Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Published online December 08, 2025. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.24384

Secondary Outcomes

Outcome | Closed-Loop | Conventional |

|---|---|---|

28-day mortality | 224/602 (37.2%) | 218/597 (36.5%) |

Duration of ventilation in survivors, median | 3.3 days (IQR 1.0-9.4) | 2.6 days (IQR 1.0-8.7) |

ICU length of stay, median | 4.5 days (IQR 1.8-11.9) | 4.4 days (IQR 1.8-12.4) |

Hospital length of stay, median | 12.2 days (IQR 3.5-27.5) | 12.0 days (IQR 4.0-25.3) |

90-day mortality | 246/600 (41.0%) | 237/592 (40.0%) |

ARDS (developing after 48h) | 15/599 (2.5%) | 12/596 (2.0%) |

Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 13/599 (2.2%) | 21/596 (3.5%) |

Extubation failure | 32/413 (7.7%) | 30/412 (7.3%) |

Ventilation quality (subset of 152 patients, n=78 closed-loop, n=64 conventional):

Optimal zone: 48.4% vs 36.7% of time (P=0.05)

Acceptable zone: 40.1% vs 27.5% (P=0.03)

Critical zone: 11.6% vs 35.8% (P<0.001)

Safety outcomes:

Severe hypoxemia (PaO₂ <55 mm Hg): 16.0% vs 21.1% (P=0.02)

Severe hypercapnia (PaCO₂ >55 with pH <7.35): 19.9% vs 24.2% (P=0.08)

Need for rescue therapies: 14.4% vs 20.3% (P=0.006, not significant after multiplicity adjustment)

Prone positioning: 9.2% vs 13.9% (P=0.009)

Recruitment maneuvers: 5.2% vs 5.0%

Bronchoscopy for atelectasis: 5.5% vs 7.4%

Subgroup Analysis

No significant treatment effect modification observed across any prespecified subgroups:

Type of admission (medical vs surgical)

Neurological admission (yes vs no)

Cardiac arrest (yes vs no)

Hypoxemic respiratory failure (yes vs no)

BMI (>30 vs ≤30)

Severity of illness (high vs low)

Criticisms

Nearly 20% of randomized patients were excluded postrandomization because deferred informed consent could not be obtained. This is effectively a 20% loss to follow-up for the primary outcome, and it's actually worse because baseline characteristics of excluded patients are unknown. Even though exclusion rates were balanced across groups, this threatens internal validity.

The trial population was extremely heterogeneous. Only 30% were ventilated for respiratory failure. About 25% were ventilated for neurological impairment and 25% following cardiac arrest-patients who often need minimal ventilator management and remain intubated for mental status rather than respiratory reasons. This may have diluted any treatment effect from closed-loop ventilation.

Short duration of ventilation in most patients. About 60% either died (20%) or were successfully extubated (40%) within 3 days. This may not have provided enough exposure to the intervention for cumulative benefits to manifest. Closed-loop systems likely show greater advantage when ventilation is prolonged and more opportunities exist for adaptive optimization.

The control group received highly protocolized, expert-level conventional ventilation including three-times-daily weaning assessments-far exceeding usual practice in most ICUs. This represents near-optimal conventional care and makes it difficult for automation to demonstrate superiority. The trial effectively compared closed-loop ventilation to best-case conventional ventilation rather than typical usual care.

Open-label design could have introduced bias, though mortality as the key outcome component is objective. The difference in prone positioning use (9% vs 14%) is interesting given the very low ARDS rate (2% in both groups)-unclear what the indications were.

Ventilation quality outcome was measured in only a convenience sample of 152 patients (13% of the cohort), limiting generalizability of this finding. The composite outcome also relied on subjective and difficult-to-operationalize classifications.

The trial was powered to detect a 1.5-day increase in ventilator-free days, which in retrospect may have been optimistic. The actual effect size appears smaller, and a much larger trial would be needed to detect it.

No assessment of clinician workload, staffing requirements, or costs-all potentially important advantages of automated systems that weren't captured.

Secondary outcomes weren't assessed using hierarchical testing, so findings favoring closed-loop ventilation (improved ventilation quality, reduced hypoxemia/hypercapnia, fewer rescue therapies) should be interpreted as exploratory.

Dashevsky's Dissection

For patients: This trial tells us that if you're intubated in an ICU with expert-level ventilator management, adding automated closed-loop ventilation won't get you off the ventilator faster or improve your survival. You'll spend about the same amount of time on the vent and have the same chance of dying regardless of which approach is used. The automated system did reduce episodes of dangerously low oxygen and high CO₂, but those improvements didn't translate into meaningful clinical differences.

For pulmonary and critical care physicians: ACTiVE is one of the largest and most rigorous trials of mechanical ventilation ever conducted in the ICU, and its neutral findings matter. But we need to interpret them carefully.

The trial tested closed-loop ventilation against near-optimal conventional care-three-times-daily weaning assessments, strict adherence to lung-protective ventilation, protocolized sedation management. That's not what happens in most ICUs. If closed-loop ventilation performs equivalently to best-case conventional ventilation while potentially reducing clinician workload (not measured here), that could still represent meaningful value in resource-constrained settings.

The patient population likely diluted treatment effects. When a quarter of your cohort is intubated for depressed mental status following cardiac arrest and another quarter for neurological impairment, you're enrolling a lot of patients who don't need sophisticated ventilator management. They need minimal settings and time. Closed-loop ventilation probably offers the most benefit in patients with true respiratory failure-particularly those with ARDS, poor compliance, elevated respiratory drive, and ongoing lung injury risk. Only 15% of this cohort had hypoxemic respiratory failure.

The short duration of ventilation compounds this issue. Sixty percent were off the vent or dead within 3 days. The cumulative advantages of breath-by-breath optimization probably require more time to manifest. If you're only on the ventilator for 2 days with relatively preserved lung mechanics (driving pressure was 13 cm H₂O in both groups), automation has limited opportunity to show benefit.

The ventilation quality finding is interesting but needs cautious interpretation. The closed-loop group spent more time in "optimal" ventilation zones and less in "critical" zones. Severe hypoxemia and hypercapnia were less frequent. Prone positioning was used less often (9% vs 14%). But these didn't translate into clinical benefit. This could mean:

The improvements weren't clinically meaningful

The conventional group's physiology was "good enough" even if not optimal, or…

The short duration of ventilation prevented small physiologic advantages from accumulating into clinical differences.

The 20% postrandomization exclusion rate is concerning from a methodological standpoint. I understand the ethical requirement for deferred consent, but it creates a scientific problem. We don't know the baseline characteristics of excluded patients. Even though exclusion rates were balanced across groups, this is effectively missing data for the primary outcome in one-fifth of randomized patients. It's worse than typical loss to follow-up because we can't even characterize who was lost.

For the health system: This is where things get complicated. The trial didn't measure clinician workload, and that's a missed opportunity. If closed-loop ventilation delivers equivalent outcomes with less intensive human oversight, that could justify adoption even without superiority in patient-centered outcomes. Three-times-daily weaning assessments are resource-intensive. Most ICUs don't do this. If automation can match that level of performance without requiring three respiratory therapist assessments per day, that's a win.

But we need more data. The trial was conducted in 7 centers with extensive experience using INTELLiVENT-ASV. Implementation in less experienced centers might not go as smoothly. And the trial doesn't tell us whether closed-loop ventilation outperforms typical usual care-only that it matches expert protocolized care.

Future trials should focus on higher-risk patients-those with ARDS, poor compliance, anticipated prolonged ventilation. A noninferiority design comparing closed-loop to protocolized conventional ventilation in that population, with careful attention to clinician workload and cost, would be valuable. If you can show noninferiority with reduced resource demands in the population most likely to benefit, you have a case for adoption.

The broader question is about the role of automation in critical care. We're chasing marginal gains in increasingly optimized systems. When conventional care is already highly protocolized and expertly delivered, automation has less room to improve. The value proposition shifts from "better outcomes" to "equivalent outcomes with less effort." That's still valuable, but it's a different argument.

Sinnige JS, Buiteman-Kruizinga LA, Horn J, et al. Effect of Automated Closed-Loop Ventilation vs Protocolized Conventional Ventilation on Ventilator-Free Days in Critically Ill Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Published online December 08, 2025. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.24384