The American Heart Association published updated guidelines for post-cardiac arrest care, and they're packed with practice-changing recommendations that every intensivist needs to know.

We're talking about new temperature targets, updated prognostication timelines, a fresh serum biomarker entering the picture, and clearer guidance on when to pull the trigger on coronary angiography. If you're managing post-arrest patients in the ICU—and most of us are—this is required reading.

Context: What's New and Why Now

The 2025 guidelines (Part 11 of the AHA's CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care series) represent the latest synthesis of post-cardiac arrest evidence. Published in Circulation this October 2025, they build on prior recommendations but incorporate new data on temperature management, neuroprognostication, and emerging biomarkers.

These updates come at a time when cardiac arrest affects up to 700,000 people in the U.S. annually. Survival rates remain low, but post-arrest care has evolved significantly—and these guidelines reflect where the evidence has landed.

The writing group reviewed systematic literature through November 2024 and leaned heavily on the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus statements, so this is as evidence-based as it gets.

Key Recommendations

1. Temperature Control: Wider Range, Same Duration

Recommendation: Target a constant temperature between 32°C and 37.5°C for at least 36 hours in comatose patients after cardiac arrest.

Evidence Grade: Class 1, Level B-R (strong recommendation, moderate-quality randomized evidence)

What This Means: You have more flexibility than before. The key is avoiding fever and maintaining any controlled temperature in that range—not chasing a specific number like 33°C. Consistency matters more than the exact target.

2. Oxygenation Targets: Avoid Hyperoxia

Recommendation: Maintain SpO₂ between 90–98% after ROSC.

Evidence Grade: Class 1, Level B-R

What This Means: Liberal oxygen is out. Tight control prevents oxidative injury without risking hypoxemia. This is straightforward to implement and applies to every post-arrest patient you manage.

3. Ventilation: Normocapnia is the Goal

Recommendation: Target PaCO₂ of 35–45 mmHg.

Evidence Grade: Class 1, Level B-R

What This Means: Both hypercapnia and hypocapnia can worsen neurologic outcomes. Aim for the middle and avoid extremes—especially in the first 48 hours.

4. Blood Pressure: Keep MAP Above 65

Recommendation: Maintain mean arterial pressure ≥65 mmHg to optimize neurologic recovery.

Evidence Grade: Class 1, Level B-NR (strong recommendation, moderate-quality nonrandomized evidence)

What This Means: This is your floor, not your ceiling. Some patients may benefit from higher targets, especially if they're chronically hypertensive, but 65 is the evidence-backed minimum.

5. Neuroprognostication: Wait at Least 72 Hours

Recommendation: Use a multimodal approach and delay prognostication until ≥72 hours after return to normothermia.

Evidence Grade: Class 1, Level B-NR

What This Means: Don't rush it. Combine clinical exam, EEG, imaging, and biomarkers. Early withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy based on single findings is a setup for error. The addition of neurofilament light chain (NfL) as a serum biomarker gives us another tool in the prognostic arsenal alongside NSE.

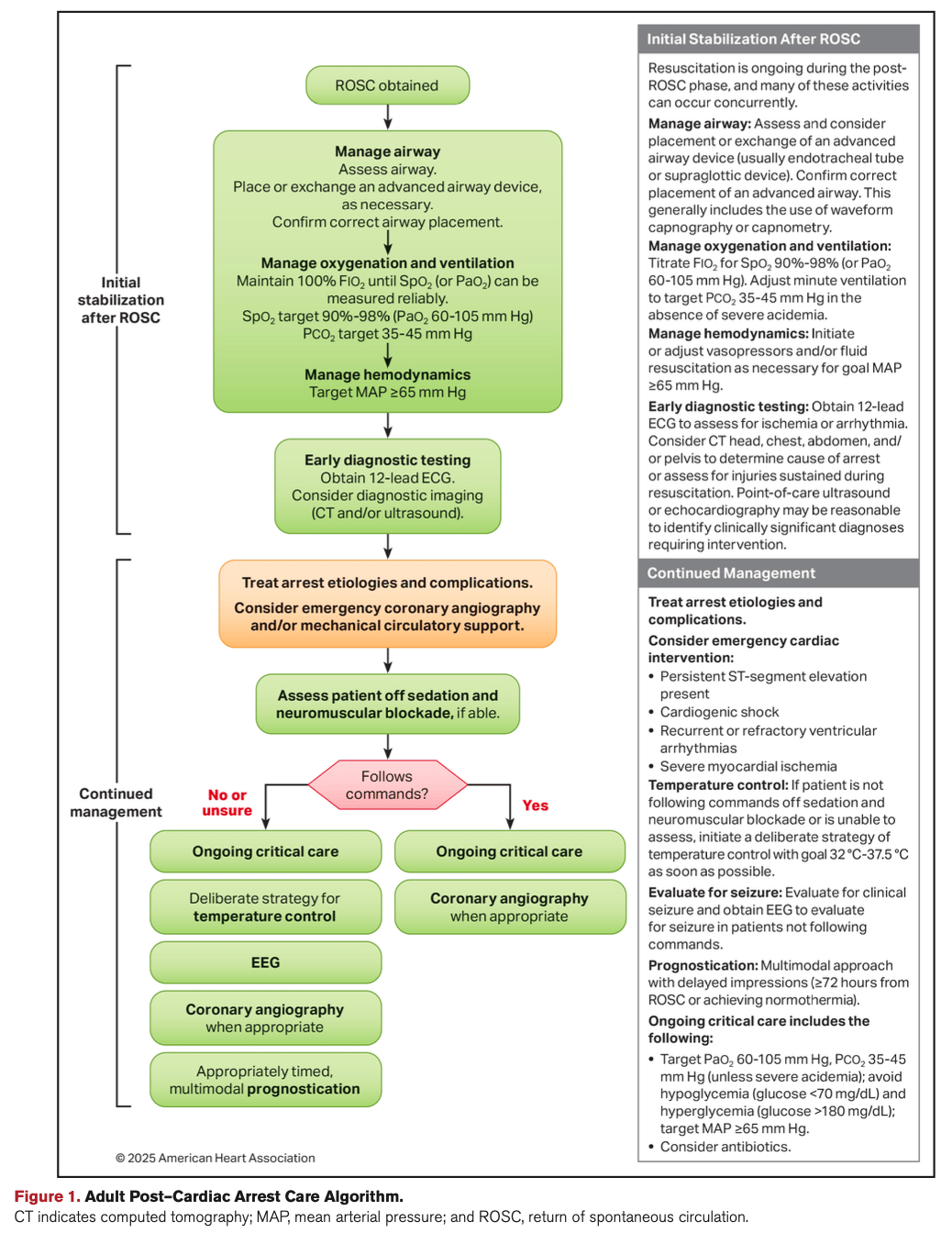

Source: AHA

What Changed From Prior Guidelines

The 2025 update expands the acceptable temperature range (previously narrower targets were emphasized), formalizes the role of neurofilament light chain (NfL) as a prognostic biomarker, and adds new guidance on myoclonus management—specifically advising against treating myoclonus without EEG correlate.

There's also stronger language around coronary angiography: it's now recommended prior to discharge for cardiac arrest survivors with suspected cardiac etiology, particularly those with shockable rhythms. This reflects growing evidence that early cath lab access improves outcomes in select patients.

On the flip side, routine use of mechanical circulatory support is explicitly not recommended unless you're dealing with highly selected cases of refractory cardiogenic shock. The data just isn't there to support broad use.

Controversies and Limitations

Not everything here is settled science. The temperature debate continues—some centers swear by 33°C, others have moved to 36°C, and the guidelines essentially say "pick one and stick with it." That flexibility is both liberating and frustrating, depending on how you like your protocols.

The multimodal prognostication framework is evidence-based but resource-intensive. Not every hospital has continuous EEG, timely MRI access, or the ability to send NfL levels. The guidelines acknowledge this gap but don't offer much in the way of practical alternatives for under-resourced settings.

And while the addition of NfL is exciting, it's not yet widely available or standardized across labs. Same story with some of the imaging recommendations—great in theory, harder in practice.

Dashevsky's Dissection

For Patients

Post-cardiac arrest care has historically been a black box—wildly variable protocols, inconsistent temperature management, and prognostication timelines that sometimes felt arbitrary. These guidelines standardize care in ways that directly improve survival and neurologic outcomes.

Tighter oxygenation and ventilation targets reduce secondary brain injury. Extended temperature control (≥36 hours) and delayed prognostication (≥72 hours post-normothermia) give patients more time for meaningful recovery before life-or-death decisions are made. The addition of neurofilament light chain as a prognostic tool means fewer false-pessimistic predictions—and fewer premature withdrawals of care.

For Physicians

These recommendations clarify our targets and give us a defensible framework for post-arrest management. No more guessing whether 33°C is better than 36°C—pick a number between 32–37.5°C and commit. No more debating MAP goals in a vacuum—65 mmHg is your floor.

The multimodal prognostication approach is more rigorous but also more protective. It forces us to slow down, gather multiple data points, and resist the urge to prognosticate too early based on a single exam or imaging finding. The explicit guidance against treating myoclonus without EEG correlate also prevents unnecessary interventions that don't improve outcomes.

That said, implementing multimodal prognostication is resource-intensive. Continuous EEG, timely MRI access, and biomarker availability aren't universal—and the guidelines don't solve that gap.

For the Health System

Post-cardiac arrest care is expensive, labor-intensive, and emotionally taxing. But when done right, it can save lives and restore function. These guidelines push hospitals to invest in the infrastructure that makes best practice possible: robust EEG programs, rapid cath lab access, standardized protocols, and timely prognostic testing.

The emphasis on early coronary angiography for shockable rhythms means health systems need seamless ICU-to-cath-lab workflows. The move away from routine mechanical circulatory support saves money and reduces unnecessary procedural risk—but only if intensivists and cardiologists are aligned on patient selection.

Standardizing care also creates opportunities for quality improvement. When everyone follows the same evidence-based targets, we can actually measure whether we're doing it well—and where we're falling short.

Bottom Line for Your Practice

Here's what changes:

Tighten your oxygenation and ventilation targets. SpO₂ 90–98%, PaCO₂ 35–45 mmHg. Non-negotiable.

Pick a temperature target between 32–37.5°C and stick with it for ≥36 hours. Avoid fever at all costs.

Keep MAP ≥65 mmHg. Adjust as needed for individual patients.

Wait at least 72 hours post-normothermia before prognosticating. Use a multimodal approach: clinical exam, EEG, imaging, NSE, and NfL if available.

Get early cardiology involvement. If the arrest was likely cardiac in origin and the rhythm was shockable, cath lab access should be part of the discharge plan.

Don't treat myoclonus unless there's an EEG correlate. Clinical myoclonus alone isn't an indication for aggressive suppression.

Read the full guidelines here: 2025 AHA Guidelines for Post-Cardiac Arrest Care, Circulation